PICO-8: Orbit

Published July 8, 2020

Over the past couple weeks, as a way to stretch my programming legs and play around with a new system, I've been writing a little demo in the 8-bit retro video game environment called PICO-8. Since I think I'm drifting away from this project now, I figured I might as well post my progress here: a "game" demo called Orbit that instantiates a number of objects moving in an elliptical orbit around a central planet.

One of the neat things about PICO-8 is how easy it is to embed a playable demo! Here is the full program running in your browser:

The program starts by instantiating 5 orbiting objects around a central planet. You can switch which object you're focusing on using ← and →. The two primary buttons (defaults to C and X on a desktop, or onscreen keys on mobile) allow access to the menu at the top-right. The menu has functionality for speeding up or slowing down time, adding and removing objects, and changing whether orbits are displayed and what info shows up on the HUD.

This is about the third time I've recreated essentially this same structure in different languages/environments. The first time was in Lua in the LOVE2D framework, the second was in Python in PyGame, and now it's in pseudo-Lua in PICO-8. I'm not sure why this construct - just getting thing to orbit each other, really - appeals to me so much. But clearly there's something there.

Each of the orbiting objects is "on rails" in a sense - rather than apply some kind of gravitational force each timestep, each object is locked into a perfect elliptical orbit defined by four orbital parameters (semi-major axis, eccentricity, argument of periapsis, and mean anomaly at epoch. Given a time T and those four parameters, the engine can calculate exactly where each object should be. Then we just let T advance at some fraction/multiple of real time.

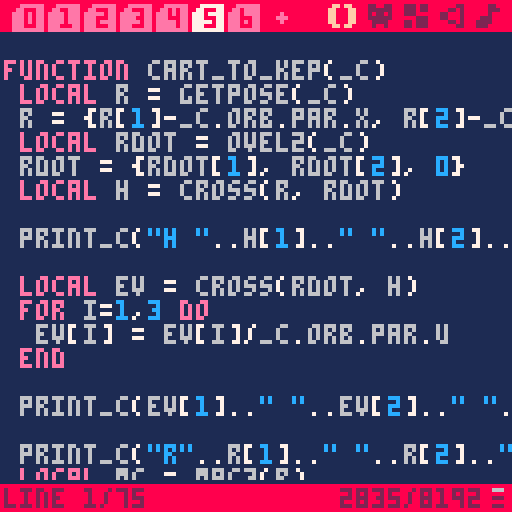

The next step in turning this into some kind of actual game would be to allow the orbiting objects ("ships") to apply a small amount of thrust that changes their orbit. This involved calculating the current Cartesian parameters (position and velocity) and turning those into new orbital parameters.

The hangup with this in PICO-8 is that all numbers are 32-bit fixed precision (0xFFFF.FFFF), with a range of -32768 to 32767.9999. While this is enough range to capture all the fundamental parameters of the orbit themselves (the largest of which is the semi-major axis, which can be up to about 200), it's not enough dynamic range to do some of the calculations for converting cartesian parameters to orbital ones. Even finding the magnitude of a 2D vector with components ~150 or greater involves an intermediate step with numbers larger than 32767, which is a problem when that's the largest number we can represent in our number system.

I briefly toyed with creating a system to present 64-bit numbers as a duo of 32-bit fixed-point ones, but it's not quite where my interests lie at the moment. So the project pauses here for now.

In any case, in encourage you to try out PICO-8 and play around. It's very approachable and a ton of fun, takes me right back to my days writing QBasic on my middle-school math teacher's computer.